The history of radio stretches back to 1867, when the Scottish mathematical physicist James Clerk Maxwell predicted the existence of radio waves with his theory of electromagnetism. Then, in the late 1880s, German physicist Heinrich Hertz proved Maxwell's theory by generating radio waves in his laboratory. The third big breakthrough came when the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi created the first practical radio transmitters and receivers in the mid-1890s, for which he received the 1909 Nobel Prize in physics.

On Christmas Eve 1906, the Canadian radio pioneer Reginald Aubrey Fessenden broadcast the first radio entertainment program as we know it today. The program was transmitted over long distances and featured music and commentary. Between 1920 and 1945, radio became the world’s first electronic mass medium, spreading culture across the airwaves and opening up other parts of the world to millions of people.

Since then, the history of radio has been defined by some truly legendary broadcasts. Here are some of the most famous, from the very first commercial radio transmission to pivotal messages in times of war and peace.

We’d appreciate it if anyone hearing this broadcast would communicate with us, as we are very anxious to know how far the broadcast is reaching and how it is being received.Leo Rosenberg

In 1920, the U.S. Department of Commerce issued the first-ever radio license to KDKA, which continues to operate in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to this day. A few days after receiving that license, the fledgling radio station went on air to broadcast the election results of the presidential race between Warren G. Harding and James M. Cox.

It was the world's first commercial radio broadcast, and it paved the way for other companies to follow suit, with 600 commercial stations springing up around the United States over the next four years.

Ladies and gentlemen, this is the most terrifying thing I have ever witnessed … Wait a minute! Someone’s crawling out of the hollow top. Someone or … something. I can see peering out of that black hole two luminous disks … are they eyes?Reporter Carl Phillips (Frank Readick)

When Orson Welles’ radio adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds aired on October 30, 1938, no one involved was prepared for the chaos that ensued. The broadcast appeared to describe the beginnings of a full-scale Martian invasion of Earth, dramatized in part through fake news bulletins.

Listeners who tuned in late missed the introductory explanation as to the nature of the broadcast, leading some to think the events being described were really happening. While reports of mass hysteria were exaggerated, many listeners did panic. Complaints from some of those listeners forced Wells to make a public apology — although the incident did wonders for his career overall.

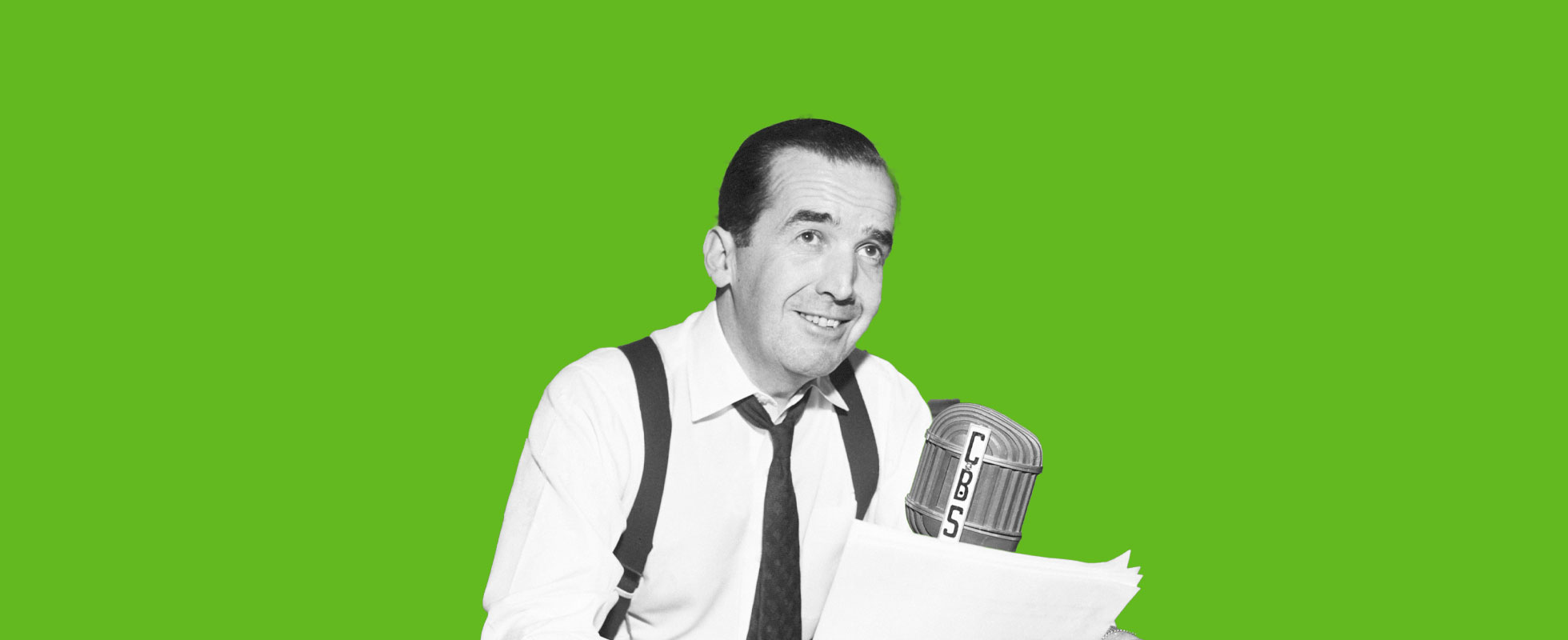

And oh, it’s … burning, oh, four or five hundred feet into the sky. It’s a terrific crash, ladies and gentlemen. The smoke and the flames now and the frame is crashing to the ground, not quite to the mooring mast. Oh, the humanity!Herb Morrison

Herb Morrison’s 1937 eyewitness report of the Hindenburg disaster is just as chilling now as it was then. Morrison’s emotional yet professional account of the explosion and crash of the German passenger airship wasn’t broadcast live, but its impact upon its release the following day was immediate. It remains one of the most famous broadcasts in the history of radio journalism.

One of the strangest sounds one can hear in London these days — or rather these dark nights — [is] just the sound of footsteps walking along the streets, like ghosts shod with steel shoes.Edward R. Murrow

Edward R. Murrow’s voice became well known during World War II, initially through his regular live broadcasts from a studio in the subbasement of the BBC’s Broadcasting House in London.

But it was when Murrow decided to venture out of the studio that he really brought the war into the living rooms of American homes. In 1940, his special program, London After Dark, captured the sounds and feelings of the Blitz, and his masterful way with words contributed to what is still regarded as some of the finest radio journalism ever recorded.

Hier ist Gustav Siegfried Eins. Es spricht der Chef. (Translation: This is Gustav Siegfried Eins. The Chief is speaking.)Peter Seckelmann

On the evening of May 23, 1941, German soldiers heard something incredible coming over the airwaves: a tirade of criticism aimed at the incompetence and corruption of the Nazi leadership. This kind of criticism was unheard of, given the nature of Nazi state media.

Nonetheless, here was the voice of a devoted Nazi and military veteran, Gustav Siegfried Eins (aka “the Chief”), railing against his own leaders. But his listeners were unaware of one important detail: None of it was real. It was in fact a British black propaganda radio station aimed at impairing enemy morale, and “Gustav” was in fact Peter Seckelmann, a German exile and journalist who’d fled to England in 1938. The ruse was highly effective and proved to be a constant thorn in the side of the Nazis who tried — and failed — to shut it down.

Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.Franklin D. Roosevelt

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was well known for his fireside chats, a series of 31 evening radio addresses that he gave between 1933 and 1944. However, his most famous radio broadcast came the day after the Japanese attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. His “Day of Infamy” speech stirred Americans into action, prompting Congress to nearly unanimously declare war against Japan, forever changing the trajectory of U.S. history as well as World War II.

A right to the body. A left hook to the jaw. And Schmeling is down! The count is five … Five, six, seven, eight … The men are in the ring; the fight is over on a technical knockout. Max Schmeling is beaten in one round!Clem McCarthy

Few sporting events in history have captured the public imagination like the two bouts between the American boxer Joe Louis and the German Max Schmeling, the first in 1936 (won by Schmeling) and the second in 1938 (in which Louis knocked out Schmeling in the first round).

Not only did the fights represent the conflicting ideologies of the United States and Nazi Germany, but they also characterized the racial struggle in America, with Louis being a massive source of Black pride in a segregated nation. Billed as the “Fight of the Century,” the 1938 fight attracted possibly the largest audience in history for a single radio broadcast, with some 70 million Americans — more than half the population at the time — tuning in.

Featured image credit: Bettmann via Getty Images